PART THREE: A Disrespectful Racket.

For most early British converts the painful discovery that they had not been fully informed concerning the true nature of what Fanny Stenhouse called “practical Mormonism”, did not take place until they arrived in America, by which time there was little realistic opportunity of turning back. However, some British members did catch a glimpse of things as they actually were through their close association with the American leaders of the church in Great Britain, and how they privately conducted themselves.

Samuel Hawthornthwaite was an elder in the Hulme Branch in Manchester in 1850, at a time when the growth of the 19th century British LDS church was nearing its zenith. At that point Cyrus Wheelock, (who had been a close friend and confidant of Joseph Smith at the time of Smith’s assassination in 1844), was called to preside over the Manchester Conference, (i.e. District), and Hawthornthwaite kindly offered accommodation in his home to Elder Wheelock and his English wife, whom he had recently married[1]. An ugly rumour was already in circulation however, (and it was subsequently shown to be true), that Wheelock had another wife or perhaps wives back in America, and so Hawthornthwaite, not wishing to be an accessory to bigamy, privately confronted him about the matter, whereupon Wheelock issued strenuous denials and assurances.

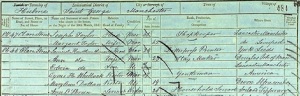

Nevertheless, within a short time complaints arose against Elder Wheelock because of his“making too free with the younger sisters in the country branches”, concerning which conduct, Hawthornthwaite noted, even non-Mormons had begun to comment. Wheelock’s response was to deny all accusations, and to take disciplinary action against those members who had dared to accuse him of such predations. Continues Hawthornthwaite: “When he had been at my house a few months, he persuaded his wife to go and live with her friends at Birmingham, and in her stead, he brought a Miss Dallan, from Newport, where he had been preaching.” This part of the narrative is borne out by the 1851 census of 45 Clare Street, Hulme, in which it was recorded that Mary Ann Dallan, aged 19, a native of Ilfracombe, Devon, was staying with Cyrus H. Whellock (sic), a Gentleman, in the Hawthornthwaite household.

1851 Census enumeration of Samuel & Ann Hawthornthwaite’s household at Hulme.

The Hawthornthwaites were somewhat disconcerted that there appeared to be an inappropriate degree of intimacy between Elder Wheelock and young Sister Dallan, but nevertheless accommodated her as a guest, by altering the household sleeping arrangements. However, Miss Dallan soon affected to be unwell, and took to her bed, asking Wheelock to “lay hands” upon her, (i.e. to give her a priesthood blessing), to ease her sickness. After that Wheelock assured Hawthornthwaite he would sit up and look after the young woman each night. This aroused Sam Hawthornthwaite’s suspicions, until he, his wife and other witnesses one morning observed the couple sleeping together in bed. Mrs Wheelock was privately sent for, and when she arrived in a state of distress, Mrs Hawthornthwaite told her all that had taken place. Wheelock and Miss Dallan were out together at the circus that particular evening until 11.30pm, so were unaware that Mrs Wheelock had arrived in their absence. The couple returned in a state of some jollity, only to be confronted by the wronged wife.

In addition to the act of adultery, Elder Wheelock had also spent an estimated £90 on the wooing of Miss Dallan over the course of six weeks, and that money had come from donations made by the downtrodden members of the Manchester Conference. “He bought her three new dresses… boots, bonnets, ribbons, shawls, pomatums, paints, scents, in fact everything a capricious girl could wish, or an old fool lavish. He took her to the boxes of the Theatre Royal five nights out of six, where he fed her with wine, jellies, cakes, oranges, and the like, to such an extent, that when she emptied her pockets in the morning, there was enough of broken bits to feast my little boy during the day. This he did, while the Saints were starving themselves on his account.” Wheelock was in effect using the widows’ mites to further his own amorous ambitions, and so out of a sense of acute injustice, Hawthornthwaite attempted to hold his Conference President to full account before the church on charges of adultery and extravagance.

However, Wheelock’s reputation for vindictiveness, acquired when he had been previously accused of wrongdoing, was enough to persuade some witnesses to withdraw their evidence, for fear that they would in the process lose their membership, and with it, as they believed, all eternal hope. In the hour of their testing, loyalty appeared more important to them than truth. Even Hawthornthwaite’s branch president, who had previously complained to him that for fourteen years the Americans had been the greatest curse the English members had had to endure, when it really counted bore a hypocritical testimony to a church court, (held over the course of three consecutive evenings), that without servants of the Most High like Wheelock the British would have no salvation available to them. Unsurprisingly, Wheelock denied all the charges, whereupon the presiding officer, Elder Wallace, another American, dismissed the case as unproven, commenting: “I know it is hard to make you Englishmen believe that a servant of the Lord can sleep with a young lady for three weeks, and not commit adultery with her, but it is so.” Undoubtedly, Wallace, like Wheelock, already had knowledge of the secret system of plural marriage which was being practised in America, but it was not until the following year that this was officially revealed as a doctrine and practice of the church, and until then the British members were “protected” from hearing it, unless, of course, they emigrated and witnessed it first-hand.

Cyrus Wheelock, one-time friend of Joseph Smith and Manchester Conference President in 1851.

Having been acquitted, Wheelock then set about cutting off from the church all who had opposed him in the hearing, and according to Hawthornthwaite’s record, used his high priestly powers to curse him and his children publicly that they might be cast “as far into Hell, as a pigeon can fly in a day!” Such a volatile outcome was perhaps always likely when an experienced American frontiersman, believing himself to be uniquely authorised of God, encountered a stubborn Englishman, (and a Yorkshireman at that), who had discerned through reasoned observation that he was not. It was not long though before others reached similar conclusions to Hawthornthwaite: when a member by the name of Harrison was excommunicated for fathering an illegitimate child, he protested to the church court:“If you cut me off, you must also cut off Elder Wheelock, for while I was in one bed with one sister, he was in another bed with the other.”

The Mormon elite were permitted some extra degree of latitude apparently. They were their own judges in this land, as no resident British member was at that time authorised to sit in judgment upon them, so their word was effectively the law of the church, and the church, of course, was God’s prescribed means of salvation. Having known, or been personally acquainted with Joseph Smith, Brigham Young, and others, these men occupied a rarefied position in the gathering of the British people to Zion. Cyrus Wheelock, for example, was the man who had smuggled a pistol into Carthage Jail, Illinois, for Joseph Smith shortly before his death. (Smith and his brother were at the time being held, pending trial, to answer charges of treason, having destroyed the printing press of The Nauvoo Expositor newspaper, which had published details of Smith’s marital or extra-marital excesses.) Wheelock’s conduct was perhaps only in imitation therefore of that of his file leaders, whom he idolised.

Not long after Sam Hawthornthwaite found himself embroiled in troubles over the conduct of Cyrus Wheelock, Fanny Stenhouse received news from her Scottish husband, who was at the time serving a mission in Switzerland, that talk was rife among his American brethren that Brigham Young might be about to announce that the church would adopt the practice of polygamy. There had been rumours which had previously come to her ears, but they had been quickly dismissed as anti-Mormon propaganda. Upon hearing this shocking news therefore, her world fell apart: “I began to realize that the men to whom I had listened with such profound respect, and had regarded as the representatives of God, had been guilty of the most deliberate and unblushing falsehood; and I began to ask myself whether, if they could do this in order to carry out their purpose in one particular, they might not be guilty of deception upon other points? Who could I trust now? For ten years the Mormon Prophets and Apostles had been living in Polygamy at home, while abroad they vehemently denied it, and spoke of it as a deadly sin. This was a painful awakening to me; we had all of us been betrayed.”[2]

Her sentiments so eloquently recorded for posterity in those words echoed the thoughts of many of the British members at the time, and when the official announcement duly came, many began to turn away from Mormonism in the British Isles. The decline in membership from 1852 onwards, accompanied by public hostility shown to Mormons, was a feature for the rest of the century.

The real disgrace though, was that so many devout British converts had already been encouraged to commit so much on trust to a cause about which they actually knew so very little. As a matter of policy, they had been deliberately deprived of full and accurate reports by their American leaders, and this had been done in order to elicit from them the kind of life-changing commitment, from which most inevitably later found themselves unable to retreat.

If the challenges of being a British Mormon had been significant before the shock of the polygamy announcement in 1852, they suddenly became much fiercer. Mormonism had previously been an object of ridicule in Britain, but afterwards became a target for hatred and despising. The following excerpt from ‘The Bristol Mercury’ in 1857 was a fairly typical illustration of how public disliking for polygamous Mormonism was apt to spill over:

“THE MORMONS AGAIN — Thomas Ingram was charged with being disorderly, and with having thrown a stone at the Mormon Chapel in Milk Street. Sunday night P.S. 91 saw a number of people, of whom the prisoner was one, throwing stones and dirt at the door of the Mormon chapel, and at the people assembled there… Mr Inspector Bell said the row on Sunday night was a very violent one; and that the mob hunted one of the Mormon elders all through the Horsefair. Mr Barrow remarked that however much the magistrates might differ from the Mormonites in their way of pursuing their religious calling —

Mr Herapath (interrupting) — Don’t call it religious. It is not that, and certainly not moral. It is a disgrace to England that we are obliged to permit these people.

Mr Barrow said that might be so, but the peace must not be broken.

Mr Herapath — Certainly not.

Mr Barrow — The magistrates would therefore call on the prisoner to find sureties, himself in £20, and two others in £10 each, to keep the peace for the future.”[3]

A mid-19th century Petty Sessions Court

The public perception from the first had been that ignorance was the reason British people were deceived by Mormonism. “It is surprising”, reported the Worcester correspondent of the ‘Morning Post’ on 4th November 1846, “even to those who know the exceeding lack of education in the rural districts of this county, and its neighbour Herefordshire, that so clumsy an imposture, and so ungainly a set of adepts, could have succeeded so well, as, unhappily, too many wretched dupes can testify.” [4] The question arises as to whether that “ungainly set of adepts” really believed in the message they were spreading? Undoubtedly the answer to that reasonable question is that they did. The great majority of missionaries by this time were British, and being recent converts themselves, trusted fully in the message they carried. They were the ones who bore the main burden of taking Mormonism to their fellow citizens under the direction of a few American leaders, and they earnestly believed that they were living during the end times of a fallen world.

Some of the earliest converts had met and listened to Apostle Wilford Woodruff during his highly successful mission to England in 1840-1, so it is not difficult to imagine the profound effect on those men and women when they read Woodruff’s words in ‘The Millennial Star’, their own LDS newspaper, in 1845; Woodruff proclaimed: “You live in the day and hour of the judgments of God Almighty… Thrones will be cast down, nations will be overturned, anarchy will reign, all legal barriers will be broken down, and the laws will be trampled in the dust. You are about to be visited with war, sword, famine, pestilence, plague, earthquakes, whirlwinds, tempests, and with the flame of devouring fire…. the slain of the Lord will be many.”[5] Little wonder then that those men called to serve missions had fire in their souls as they ventured forth into a sick and dying world with, as they believed, the single ultimate solution: Mormonism. Any personal rejection they encountered along the way merely strengthened their faith that the end was nigh. A Book of Mormon witness, Martin Harris, referring to that publication, had once stated, ”All who believed the new bible would see Christ within fifteen years, and all who did not would absolutely be destroyed and dam’d.”[6] Christ’s return, it seems, had at one time, early in the church’s history, been expected by 1846, and a similarly fatalistic outlook seems to have infected not only Woodruff, but his many British converts.

A good illustration of this is the case of Henry Glover. In the summer of 1840, Apostle Brigham Young selected Glover to leave his native Ledbury and open up the work in the city of Bristol, 40 miles away. Glover was a former preacher of the United Brethren, a localised splinter group of the Primitive Methodists, which group had converted en masse a few months earlier, under the instruction of Woodruff, believing Mormonism to be a fulfilment of their spiritual aspirations. Young described Glover in a letter to Joseph Smith as “a humble, good man, and will do much good”. However, as Young in later years recollected, Glover “went to Bristol, and cried, ‘Mormonism,’… and no person would listen to him. On the next morning he was back at Ledbury, and said, ‘I came out of Bristol, washed my feet against them and sealed them all up to damnation.’” [7]

Here then is a clear example of the apocalyptic mindset of those early British Mormons. Anticipating an imminent return of Christ, Glover, in his religious fervour, had apparently felt justified in condemning a whole city of 140,000 citizens, because a token sample of its populace had rejected in a single afternoon what he himself had recently accepted as the one true gospel! Glover was promptly returned to Bristol however, and persevered for a while longer the second time, for Woodruff’s journal records on 14th September 1840 that the Bristol Branch consisted then of Elder H. Glover, and three others.[8]

Bristol in the mid-19th Century

For a few years following the exodus of the church from Nauvoo to the Rocky Mountains in 1846/7, very few American brethren remained in Great Britain. Fanny Stenhouse records that in 1849 there were only two or three Americans in total preaching the gospel, so virtually the whole burden had fallen upon the British, and this also coincided with the greatest period of LDS success enjoyed in Britain during the 19th century. She noted that“Mormonism was bold then in Europe — it had no American history to meet… polygamy was unheard of as a doctrine of the Saints, and the blood-atonement, the doctrine that Adam is God, together with the polytheism and priestly theocracy of after years were things undreamed of.”[9]

So what was the message British Mormons were teaching in the halls and streets and market places at that point? Fanny Stenhouse explained that it was: “The saving love of Christ, the glory and fulness of the everlasting Gospel, the gifts and graces of the Spirit, together with repentance, baptism, and faith… and who can wonder that with such topics as these, and fortifying every statement with powerful and numerous texts of Scripture, they should captivate the minds of religiously inclined people?”

Even so, proclaiming this watered-down version of Mormonism was a challenging enough undertaking, especially for those who had no former experience of preaching. Of those who were called to do so, (and this was an era when male members were not automatically given the priesthood, and relatively few were ordained elders), most set about it with typical British stoicism and workmanlike determination. They did so because they believed that they were God’s vessels for bringing salvation to a dying world. Richard Rawle, a native of Devon who had been baptised in Bristol in 1842, was a fairly typical example of such men. A humble cobbler during the working day, he spent much of his spare time preaching the gospel to his fellow citizens of Bristol in ad hoc open air meetings. On two occasions he was chased by mobs through the streets after preaching, and feared he would be badly beaten or killed if caught, but still accounted himself blessed to be entrusted in this way with God’s word[10]. Mormonism may have been publicly despised, but in everyday situations individual Mormons seem to have been tolerated. William Jefferies, commenting on his interactions with non-LDS work colleagues in the 1850s stated that he had been “party to many a little ‘mormon’ debate with Sunday religionists who were my fellow-workmen, and although they pitied yet they respected me.”[11]

Two of Bristol’s home-grown missionaries, (Left) Richard Rawle, (Right) William Jefferies

The more able British male converts were sometimes called to serve missions away from home for weeks or months at a time, usually within a day or two’s walking distance from their homes. They covered an extraordinary number of miles on foot, hitching an occasional ride, and often simultaneously supported themselves by working at their trade as opportunity presented itself along the way. Many of their contacts occurred while walking from place to place. William Jefferies wrote that it had been when he was 17,“during the first few days of Jan. 1849, that I first heard ‘Mormonism’ as it is commonly called, from an Elder of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter day Saints… I was going from Coleford where my father resided, to Stoke Lane, to visit an uncle by the name of Taylor, when I met with Elder Edward Hanham… He was peddling tea and preaching the gospel, and he talked to me about the Church and its doctrines.” Conversations were not always so religiously themed however. William Willes, an American, recorded in his diary for 1st March 1864, “Left Bath, in the morning, on foot: I fell in with a lame man on the road, who was very talkative: and among other matters he stated that he once hiked with a man, who was a great drinker & who had an attack of the “Ringle Tringdums,” (Delirium Tremens). In a short time we were overtaken by a butcher, with a horse & cart, who gave us a lift nearly 8 miles from Bristol. I paid the turnpike fee for my ride.”[12]

Most of the Americans, who oversaw and participated in the work, evidently believed in the prophetic powers and divine calling of Joseph Smith, and by inference their own providential calling to direct matters as they saw fit among the British saints. Probably few were as cynical and opportunistic as Hawthornthwaite portrayed Wheelock to be, although it is clear from contemporary accounts that the American leaders generally expected and were afforded preferential treatment. They had been called for a season to perform a challenging work in a strange land. They knew the mysteries of the kingdom, which they had received in the Endowment House, and to which the British were not party. Their knowledge of how the church functioned at headquarters was therefore superior. The means whereby desired ends were accomplished were ultimately of secondary importance. It did not matter that British converts were systematically deprived of knowledge concerning certain key “higher principles” of the gospel, or were left woefully unaware of the hellish struggle which their Zionist ambitions would bring them; in mid-19th century Mormon eschatology, Zion was still a far better place to be than “Babylon”, and gathering in the harvest of souls, (including for some a plural wife or two who would accompany them back to America), was what most counted. Pious lies were justifiable therefore.

However, when one considers from a modern perspective the evident sleight of hand with which early Mormonism in Britain was dispensed by a few “in the know” men who occupied the upper echelons, surely all but the most dyed-in-the-wool Mormons today would acknowledge, (as a significant number of the converts themselves later did), that in the 19th century Mormonism was routinely mis-sold to the British public. It becomes difficult to dismiss entirely from mind the idea, (regardless of how one might view today’s LDS church and culture), that the whole exercise was actually a disrespectful racket which mainly targeted the disenfranchised and uneducated.

Of course, for the sake of current public relations, it is absolutely essential that those early missionary endeavours be represented as having been in every respect honourable and full of faith. Equally, in order to foster an illusion of continuity in purpose, it must now be made to appear that British converts who migrated to America in the 19th century, did so in order to build up and strengthen the church so that it might in the subsequent centuries mount its present global mission. The problem with that concept, which is very popular within Mormonism today, is that it is not what the converts actually believed they were doing when they did it. Mormonism has endured because it is skilful at reinventing itself and its historical narrative from generation to generation. The plain truth is that those early British converts were living in their present, a very different present than our own, and considered themselves to be fleeing spiritual Babylon no less, (Great Britain), to avoid the scourges which they had been led to believe were about to be unleashed; they were seeking physical and spiritual refuge in God’s place of safety, Zion. Fear underpinned by a certain sense of elitism, is what induced them to forsake for ever their homes, their employment, and their unbelieving relatives and friends. This is more than clear from voyage notes like those recorded for the emigrant ship ‘George Washington’, which sailed from Liverpool for Boston on 28th March 1857: “During the meeting several hymns suitable to the occasion were sung by the brethren and sisters in a spirited manner, one of which was — ‘Ye elders of Israel come join now with me,’ &c., with the chorus ‘O Babylon, O Babylon, we bid thee farewell, / We’re going to the mountains of Ephraim to dwell.’ All hearts seemed to be filled with joy, peace, and praise to their Heavenly Father for his goodness in giving them an understanding of the gospel, for making known to them that the hour of his judgments (upon Babylon) were at hand, and for making a way for their deliverance.”[13]

Mormon emigrants on deck between Liverpool and Boston

Mormonism succeeded in accomplishing its purposes in 19th century Britain to the extent that it did, largely because those overseeing the operation were prepared to cultivate the credulity of rank-and-file members year after year. They did so in order to produce a steady flow of human cargo, which commodity was to be used in establishing an American theocratic community, and it was done in the questionable belief that it was necessary that God’s chosen people be located in one place. Some may even see subtle parallels in those aims with their experience of Mormonism today. To be cynical, the all-consumingly important gathering of Israel, first to Nauvoo, and then to Utah, was ultimately about seizing and maintaining political power and identity, in the name of God, although of course that is not how Mormonism was ever promoted on Britain’s streets.

When the resulting cost in terms of human misery is taken into account, and weighed in the balance against the oft-shared faith-promoting material which understandably emanates from proud descendants of those who managed to endure the gathering process, that increasingly redundant Zionist worldview will be concluded by many to have been a social misjudgement, and a costly irrelevance. Further, it will with good reason be argued that the true legacy of the British Mormon experience, powered as it was by pious deception and spiritual manipulation, is an embarrassingly incongruous one for an organisation which today still proudly proclaims itself to be the only true and living church, with Jesus Christ having directed its progress throughout.

And this will become a stubborn legacy which will probably never be entirely shaken off by Mormonism until the full spectrum of the historical record is confronted and embraced with courage and honesty, and until a sense of genuine compassion and remorse is felt for those who, through a combination of circumstances and unrealisable promises, were eventually cast in the roles of victims and losers.

(to be continued)

[1] Samuel Hawthornthwaite. Mr Hawthornthwaite’s Adventures among the Mormons as an Elder during eight years. (Hulme, Samuel Hawthornthwaite, 1857). pp112-115.

[2] Fanny Stenhouse. “Tell It All”: The Story of a Life’s Experience in Mormonism(Hartford: A. D. Worthington and Co., 1875). p 130.

[3] The Bristol Mercury (Bristol, England), Saturday, October 17, 1857; Issue 3526.

[4] “Fortunes of a Mormonite”, The Morning Post, (London, England), November 04, 1846; Issue 22751.

[5] Wilford Woodruff, Millennial Star, v. 41, p. 241

[6] Martin Harris, The Telegraph (Painesville, OH), March 15, 1831, v. 2, no. 39

[7] “4:305”, Journal of Discourses of the General Authorities of the LDS Church, accessed May 10, 2011, http://www.journalofdiscourses.org/volume-04

[8] “The Church in Bristol 1840 – 1911”, Mormon History, accessed May 10, 2011,http://www.mormonhistory.org/index2.php?option=com_content&do_pdf=1&id=41

[9] Fanny Stenhouse. “Tell It All”: The Story of a Life’s Experience in Mormonism(Hartford: A. D. Worthington and Co., 1875). pp 48-49.

[10] “Incidents From The Life Of Richard Rawle as told by Maybelle Millet Rawle, granddaughter-in-law of Richard Rawle, also of Morgan, Utah, Summarized by Dale S. King”, accessed July 14, 2010,http://www.fortunecity.com/millenium/grangehill/246/richardrawle.htm

[11] “The Journal of William Jefferies”, William Jefferies Website, accessed December 20, 2009, http://www.williamjefferies.org/home/journal.php

[12] Mary C. Cutler & Glenda I. C. Sharp. “The life of William Willes : from his own personal journal and writings” (Provo: Family Footprints, 1999).

[13]http://mormonmigration.lib.byu.edu/Search/showDetails/db:MM_MII/t:account/id:461(accessed August 04, 2013)

Leave a Reply